‘…Spirit of Ecstasy…’

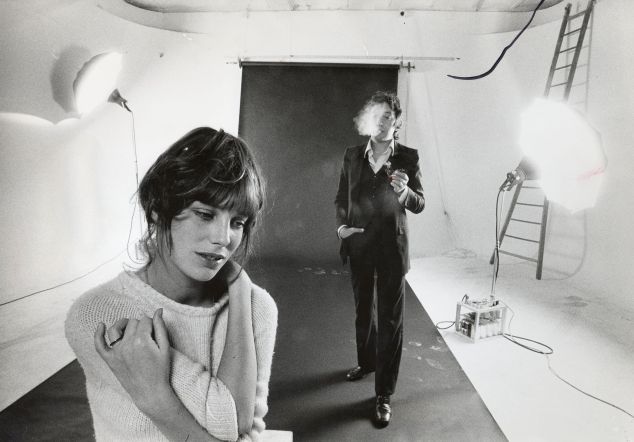

It’s 1971 and Serge Gainsbourg is driving through the French countryside in his Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost daydreaming about the car’s hood ornament, the spirit of ecstasy, designed for Lord James Montagu and modelled on his mistress Eleanor Velasco Thornton. Their affair remained hidden for over a decade until she was killed in 1915 when the SS Persia was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Fantasising about this sculpture, this ‘princess of shadows’, Serge is so entranced he doesn’t see the bicycle until the car hits it. On the road lies a girl, Melody Nelson, her skirt hiked up, her pantalons blancs showing. And so, one illicit affair inspires another. Melody is the opening track of Gainsbourg’s Lolita-esque concept album Histoire de Melody Nelson. Desire and fate, it tells us, are the same in the mind of a post-war French iconoclast. Musically it’s funky, sleepy, cinematic, cool, Serge’s seductive croon doing unspeakable things to our ears while Jean-Claude Vannier’s orchestration washes everything in drama and foreboding. It’s a trip and it’s influence has been huge, from French pop to trip hop. Beck used it on Paper Tiger, Portishead sampled the bassline for their remix of Massive Attack’s Karmacoma while David Holmes’s Don’t Die Just Yet is basically Melody with Serge removed and added beats. The original, however, remains, peerless.

‘The whole world’s shaking, shaking, shaking…’

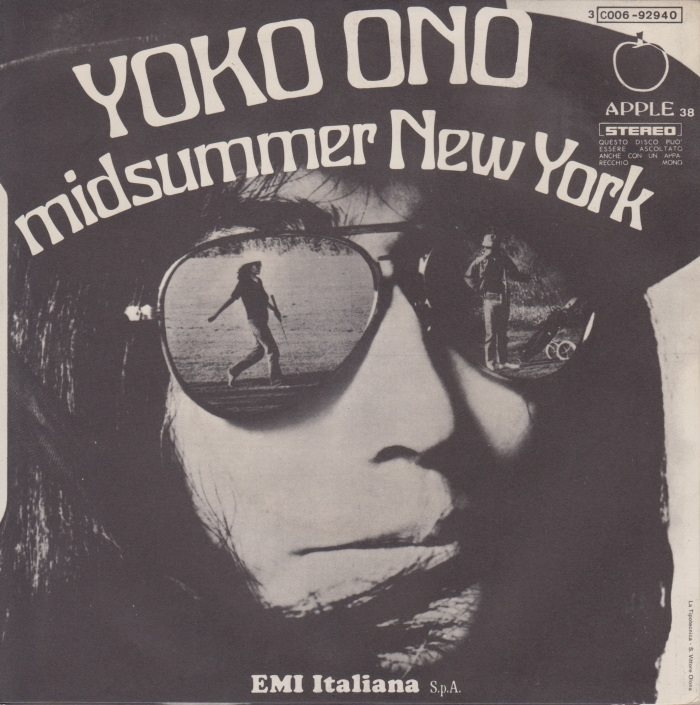

Meanwhile, in New York, the epic trolling of the Western world by Yoko Ono continues as she befuddles and outrages Beatles fans and the public in general with her idiosyncratic FLUXUS-inspired creations. Midsummer New York is from her album Fly, produced in conjunction with a film of the same name about the random wanderings of a fly on a woman’s naked body, accompanied by Yoko’s unique interpretation of what a fly sounds like. Backed by the Plastic Ono Band Midsummer New York is more straightforward musically, a febrile boogie stomp for Yoko to yell over. And yell she does, creating a proto-punk template in the process. But for all its unfettered joy it’s really a song about a mental breakdown. Even it it sounds like a typical rock-n’roll call to dance (‘shake, shake, shake!’) it’s really a cry of terror, the yelling of someone who wakes up cold with fear, who’s screaming in the mirror because everything she sees or touches is shaking, because she feels the pain of every animate and inanimate object in the world. So, musically, a blast but also terrifying.

‘I was born and I was dead…’

Meanwhile in Germany another Japanese expatriate was at the cutting edge of rock music in 1971. Kenji ‘Damo’ Suzuki was a wandering busker when Holger Czukay and Jaki Liebezeit spotted him outside a street cafe in Munich just hours before a gig. With previous singer Malcolm Mooney back to the US after a breakdown allegedly suffered while ’caught in a Can groove’ the band were in urgent need of a replacement. Suzuki’s singing, or ‘praying’, impressed them and they invited him to join the group on the spot. And he did, performing that evening even though he only knew a few guitar chords and improvised most of his lyrics. The spirit of the times. After bedding in with Soundtracks, the full Suzuki-era Can experience began with Tago Mago. Around Liebezeit’s amazing tribal wave of immersive drumming the band built worlds of surreal unease, psychedelic inner spaces, druggy, improvised grooves spliced together in the studio by Czukay using tape edits to compose the music from epic jams.

‘And deep beneath the rolling waves/In labyrinths of coral caves...’

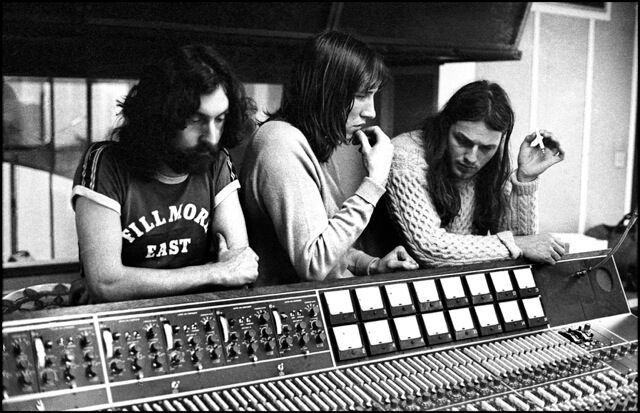

Meanwhile in London Pink Floyd are holed up in various 16-track studios messing with accidental sound effects and general I-wonder-what’d-happen-if-I-did-this experimentalism. For instance, the germ of what would become the 23-minute Echoes came when they fed a single piano note through Leslie speakers producing a submarine-like sonar ping (which proved impossible to replicate so the ping you hear on the finished track is that original one). They also fed guitars through wah wah pedals backwards and created eerie underwater effects by vibrating bass guitar strings with a steel slide and feeding the results through a Binson Echorec. Gradually, over six months, they formed this epic journey through sound that would influence music for good and ill ever since. Lyrically it’s about past, present and future, the nature of identity, the empathy we have as human beings, sea creatures, space dust. The word I’m trying to avoid is cosmic. This is cosmic music, but in a good way, not hippy incomprehension and awe, but music ‘relating to the regions of the universe…infinitely or inconceivably vast: immeasurably extended in space or time.’ It’s space rock, sure, but also time rock, ecology rock. The ambition is something else but ultimately Echoes is a monument to the creative powers of tinkering, taking things apart to see how they work, seeing machines as parts, technology as fluid, play, an uncharted frontier. (These days the individual parts wouldn’t connect as the jacks would be different sizes.) From the depths of the oceans to the outer limits of the universe, from the beginnings of time to the timelessness of space. So, yes, cosmic.

‘Gotta make way for the Homo Superior…’

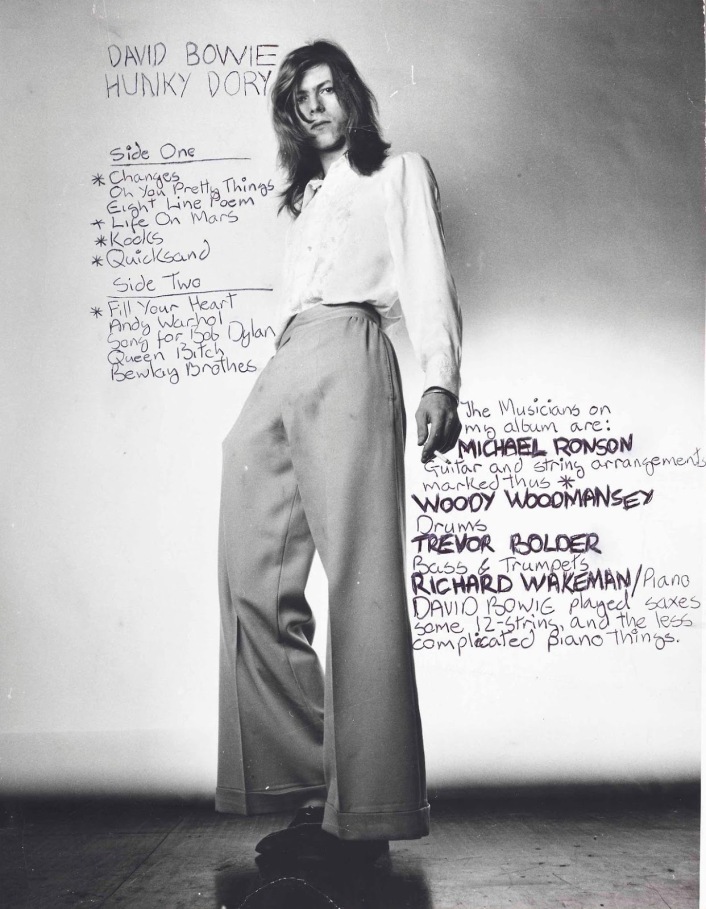

Meanwhile in another part of London David Bowie was channelling Aleister Crowley and Friedrich Nietzsche for his own version of our collective space future. The human race, as we know it, is doomed, he tells us, and the coming race will be an alliance between aliens and our children. Bowie was picking up on a metaphor for the times: the true aliens amongst us were the kids. Every fucked up teenager hearing this knew it meant them. The future was theirs and the post-war world of their parents was finished. In typical pop culture scavenging mode Bowie was fusing ideas from different sources to create a prophetic cosmic future, an evolutionary super race born of Nietzsce’s Ubermench and Crowley’s Aeon of Horus with a modish coating of space age sci-fi. Considering ‘homo sapiens have outgrown their use’, Oh, You Pretty Things is remarkably detached, jaunty even, that piano as warm as the log on the fire.

‘You make my heart feel so free…’

Meanwhile (and finally) in Philadelphia, Laura Nyro was going back to her Bronx roots with Gonna Take a Miracle, her covers album of the soul, pop, gospel and R&B she loved as a kid, her ‘teenage heartbeat songs’. Backed by vocal trio Labelle and Philly soul producers Gamble and Huff she channelled these songs through her own unique hybrid sensibility. Désiree was originally a sweet doo-wop hit for The Charts but here Nyro pares it down to a gorgeous hushed reverie, almost a swoon, love no longer a giddy teenage dream but something tender and precious, haunted by an innocence that’s not coming back, a stillness that understands it won’t last, understands that (in this spaced-out, cosmic year of 1971) all the doo-wop has disappeared.